Hotwire x Holst

Wednesday 4th December 2024

Hotwire~ is an Open Research Lab for playful experimentation with creative technology set up by Andrew Prior and David Strang. There are hotwire nodes in Plymouth, UK and Suzhou, China. We have performed, run workshops, and created installations worldwide. Hotwire is about art + technology, DIY, DIT and DIWO (Doing it Together / Doing it with Others), making / breaking stuff, hacking, creative coding and circuit bending, and more.

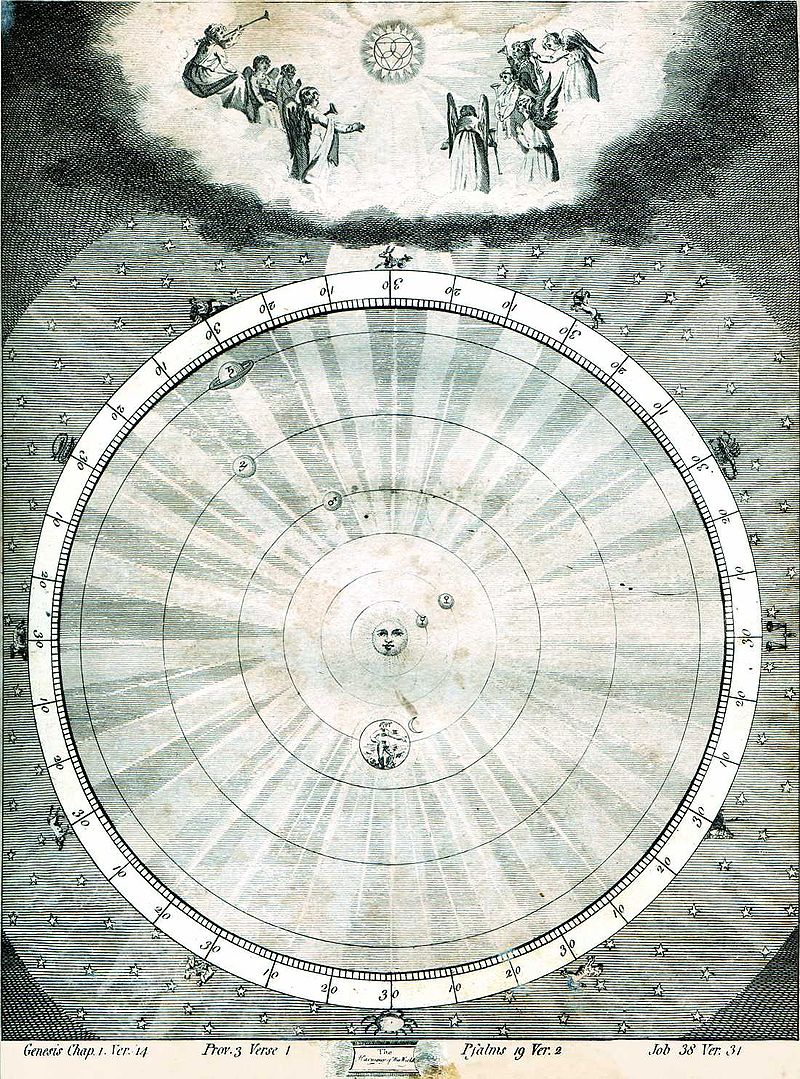

This workshop is part of the Holst Spaceship Earth project, celebrating the 150th anniversary of Gustav Holst. This event is a collaboration with PlayLa.bZ, the University of Plymouth, i-DAT, and Hotwire; and it’s happening at the Immersive Vision Theatre (IVT), a transdisciplinary instrument for the manifestation of (im)material and imaginary worlds.

Overview

In this workshop we’re going to make some sound collages. Sound doesn’t mean ‘music’ necessarily – it includes music, but also: noise, spoken word and anything else you can hear. Some of the sounds we’ll use maybe from existing sources – for example: youtube, websites, archival recordings, or sampling the music of Holst – but we can also use new sounds – poems, quotes, music instruments, handclaps, singing, humming, sound effects…